Rude awakenings can happen to any of us, at any time. Our only hope is that they won't cause too much interruption to our incredibly self-important routines, but…they're called "rude" for a reason.

My most recent one didn't hold back. It grabbed my life during a basketball game this spring, and hasn't let go since.

The play was one that was athletic, but fairly routine for me: a two-handed slam off of an alley-oop lob. I'm 6-foot-4 and have been slam dunking since I was 15, so there was no hesitation in my step. But during my takeoff on this particular evening, I felt instant pain—the shocking kind that's far too sudden and intense to shrug off.

Lying on my back on the ground, I told my friends I couldn't really feel my legs beyond the overwhelming pain. For some reason, I was afraid to look down at the damage, or even to try to turn over to assess my movement.

I silently concluded that I'd suffered a dislocation. Bad news, but not earth-shattering. My friend called an ambulance, and during the ride, I started cataloging the accessory weight-training movements I'd incorporate alongside my squats and deadlifts to prevent this from happening again.

All those thoughts came to a screeching halt when the ER doctor, after prodding around and taking some X-rays, delivered his prognosis: bilateral tendon rupture. A devastatingly serious injury. Best-case, the recovery was going to be many months, and I might never be the same again.

And I, someone who helps people get strong and move better for a living, would have to start from the bottom again—learning how to walk.

Six months later, this is what I've learned along the way.

Lesson 1: When You're Healthy, Train

For those who need the explanation, a full rupture of a tendon doesn't mean a partial tear. It means a full-scale separation, like cutting an extension cord all the way in two with a pair of heavy-duty scissors. And the "bilateral" part of the injury prognosis means this happened to both of my knees at the same time.

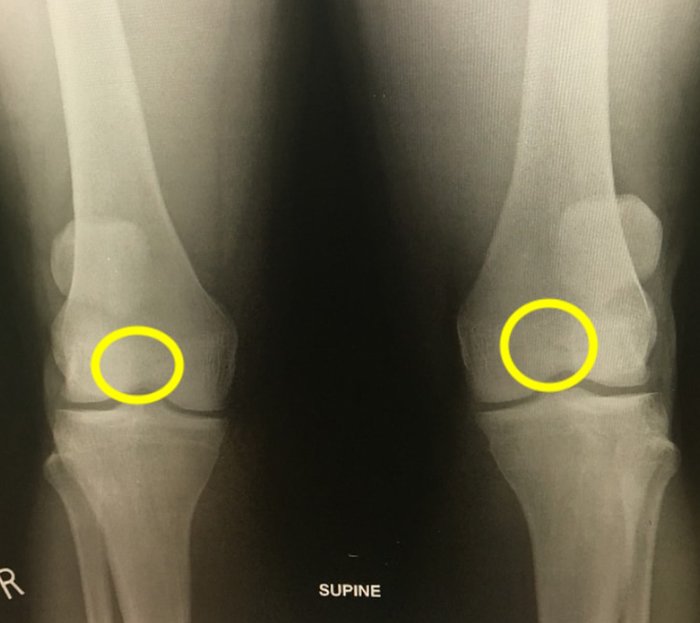

This is the actual X-ray of my legs, the day I got injured. Circled in yellow are the spots where my kneecaps were supposed to be, and as you can see, floating far above those circles is where they were newly resting—essentially up on my thighs. It was the first time anyone at the hospital had ever seen a case like this firsthand.

I would have been kept in the hospital longer than six days, but I was granted discharge for one reason: I was young and strong. I was able to demonstrate to the on-site nurses and physiotherapists that I could maneuver in a bathroom by wheeling myself to the entrance, using my upper body to essentially do a dip to the edge of the bathtub, then pulling myself over to the toilet seat.

So, the main lesson I learned is simply this: Train while you can.

As grim as the above scenario sounds, I don't know what I would have done if I was the same 260 pounds, but lacked the upper-body strength to be at least semi-functional while disabled. We train as a hobby, to satisfy our egos, and to challenge ourselves, but we often don't know how important it truly is until an event like this reminds us.

Lesson 2: Never Underestimate Your Body's Ability to Heal

At six weeks post-injury, I could bend my legs to about 25 degrees—30 if I tried hard. I still wore unforgiving straight full-leg braces and didn't take them off unless it was to gauge my range of motion while lying down. I was finally out of the wheelchair and able to bear supported load on my legs. I was becoming more dexterous with crutches.

That was the good news. The bad news was that muscle atrophy had set in, full force. I looked like Gru from Despicable Me.

All humor aside, I had to admit one thing: I didn't care about the muscle atrophy as much as I cared about the function—which was, amazingly, coming back. Surgeons had cut my knees open, pulled my kneecaps back down, and strung the tendons together to connect them back to the shin, then stapled everything shut.

And yet, I could use my legs again because the body simply "remembers" enough to restore nerve pathways and start the healing process. It was awe-inspiring to think about, even while it was nauseating to experience.

Lesson 3: Perspective is Everything

Twelve weeks post-injury, my doctor told me that progress was ahead of schedule, the procedure was a success, and I was ready to begin physiotherapy. Great news, right? Sure, except that it had taken so much to get to that point…and there was so much struggle still ahead.

Those of you who have experienced serious injury know that it's a daily mental battle. But if you stay focused on what you can't yet do, it'll lead to nothing but darkness.

I had to focus on how far I'd come, and on what I needed to do that was right in front of me. It was the only way forward.

The very next morning, I went to the gym.

Lesson 4: The Gym is A Healing Place

When I first went back to the gym, I was down close to 20 pounds due to muscle atrophy. My knees ached and I could hardly bend them to 90 degrees. But…I was at the gym. And I was going to attempt actual exercise for the first time in almost three months.

My first workout consisted of seated rows, a 135-pound bench press, and a very shallow bodyweight box squat, which proved extremely difficult.

Almost all the movements I undertook were painful. I couldn't hold a plank or push-up position because it placed unbearable amounts of pressure on my knees due to gravity. I had no eccentric control of anything requiring knee flexion. My new 6-rep max for the trap bar deadlift was literally the empty cradle.

On the page, it may not sound like a triumph. But getting back in the gym the moment I could was one of the best things that I could have done physically—but especially mentally. Exercise worked wonders for improving my mood, and this was one of those rare instances when I could feel myself getting stronger.

That said, I don't recommend anyone go out trying to bust timelines to set recovery records. Always listen closely to the recommendations of your practitioner, and also do your damnedest to learn how to listen to your body. This is an essential skill.

There will be pain to push through. That's normal—and it may even be something the doctors avoid telling you if they don't have a lot of fitness training experience themselves. But staying the course, knowing your limitations, auto-regulating your workouts, and ending all workouts on a high note to bolster your confidence is essential en route to a full recovery.

This may be a cliché, but it's true: On some days, just showing up is all it takes.

Lesson 5: Setbacks Happen

I'd be lying if I told an injured person that their recovery would happen in a straight line. It almost never does. Setbacks don't have to be complete re-injuries, they can be smaller hiccups that disrupt your linear path to better health.

In my case, I seriously aggravated my already vulnerable and tender left patellar tendon by simply standing up from a seat that was too deep, without using assistance. That stupid decision put me back a couple of solid weeks. At the same time, it refocused my thinking on taking things slow and easy.

It's sad but true: What we do in the gym matters not at all if we're rendered completely helpless by a basic life movement.

Lesson 6: Sometimes, You'll Never Be the Same

If I were an elite athlete, this injury would have ended my career. But I don't compete in a sport. I'm a 30-year-old generalist trainer whose work indirectly depends on my ability to be competent at certain movements. So, a smidge more was riding on my recovery as a coach than if I'd been an accountant, but it wasn't career threatening in my case.

With that said, it's humbling to remind myself that my knees are no longer the natural-born thing they were; they're now a giant patch job—a doctor's best attempt at recreating what they used to be.

I was never a big fan of arbitrary strength "standards" saying you must squat or deadlift this much to be "strong." I've also spoken out against dogmatized movement patterns like, "You must squat this way for it to count." But now? I'm more driven than ever to stand up against them. Maybe I won't ever cover 40 yards in 4.5 again, but really…was it incredibly important in the first place?

Lesson 7: Respect People's Limitations and Accomplishments

By 24 weeks, I had regained plenty of leg musculature (not all!), and after a long warm-up, was able to perform unassisted bodyweight squats to a below-parallel depth, and make them look fairly clean and respectable.

My amazement at my own healing was—and will continue to be—balanced by the fact that for plenty of people, this is what they have for good. I spent a month in a wheelchair living the life that others live all the time. I'm often visually reminded of this by a paraplegic lifter who is a regular at my gym.

The point is, everyone has their own limitations, and what might not seem like much to one person could be a huge accomplishment for someone else. Everyone is just doing what they can with what they have, and we should all respect that.

Lesson 8: There Are Many Types of "Performance"

At over 32 weeks, I'm now capable of a lot of gym activities, if I'm willing to do them. Like any mature adult, my body doesn't have the resilience it did when I was 18, and to add to that, it's now been through extreme trauma.

If I want to "perform" in the gym, I have to give myself the necessary prep time to do so. I may also have to choose plenty of so-called "regressed" versions of movements, simply because they serve me better.

For instance, I'm probably going to use a trap bar most of the time to deadlift from now on. And a belt. I'm also going to squat to boxes or other targets way more often than I squat free. At age 30, I have nothing to prove to anyone, and the key to lasting the test of time is to find safe ways to reap all the benefits of a movement.

But guess what? That just makes me like everyone I'm training—most are dealing with obstacles in one form or another.

The answer, I see more than ever, isn't to pretend those hurdles can be reversed. Often, they can't. The answer is to look for tiny incremental improvements between workout phases, workouts, and even between sets and reps.

Patience, care, attention, and consistency—these things make for good coaches and good clients, especially when injuries are part of the story.

If you've read this far, it may mean you've experienced something similar and can relate, or are even experiencing it now. If that's you, then take this statement to heart from probably the least sentimental person you'll ever meet: Stay the course, always consider the bright side, and celebrate the little victories. It'll get better.