Some of the most common weight training injuries involve the shoulder joint. More often than not, these injuries are due to improper form or lack of control when doing non-shoulder specific exercises. The bench press causes the majority of shoulder joint injuries. In order to have a strong shoulder joint and avoid injury, it is important to understand this complex joint. It is also important to learn about the rotator cuff and scapula in order to perform the appropriate exercises to strengthen and increase the range of motion for these structures.

The Shoulder Muscles

The Shoulder Muscles

Many people are familiar with the shoulder muscles. The primary muscles in the shoulder are known as "deltoids". There are several deltoid "heads", including the anterior (front), lateral (side), and posterior (rear). Certain exercises such as side raises or front raises isolate the various "faces" of the deltoid muscle. Compound movements like the clean and press, Arnold press, and military press are compound movements that involve the majority of the deltoid muscles.

Other upper body exercises involve the shoulder joint as well. The bench press places tension on the shoulder joint. When the bench is performed on an incline, more tension is shifted to the shoulder joint. When the flat bench is performed through an exaggerated range of motion, such that the elbows drop below the same plane as the shoulder joint (so the upper arms go below parallel with the ground) the shoulder joint is forced to rotate slightly in order to accommodate the range.

One critical component of the shoulder joint is the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that attach to the scapula (shoulder blade). The ends of these muscles attach to tendons that in turn attach to the arm bone (the humerus). The rotator cuff is what allows the shoulder joint to move in multiple directions - unlike the elbow joint, which is restrict to flexion within a specific plane, the shoulder joint is a rotary joint that may move in multiple directions. Any joint such as the hip joint or the shoulder joint that can move in multiple planes (rotate) sacrifices stability for increased movement, and therefore becomes more susceptible to injury.

One of the first ways to prevent shoulder joint injuries is to prepare the shoulder joint for stress. This means training the shoulder joint with resistance. While many people incorporate shoulder exercises into their training program, they fail to properly balance the movements or prioritize based on relative strength. As an example, the shoulder joint helps control the descent of a pull-up - the shoulder group as a vertical pushing mechanism is antagonist to the upper back group as a vertical pulling mechanism. Therefore, training between the two should be balanced, so that the volume of pull-up or pull-down movements matches the volume and intensity of shoulder pressing movements within a training cycle.

If the shoulder joint is weaker in comparison to other muscles, injury can result. A major example is the bench press. There is no exact formula to determine optimal, relative strength between the shoulder (military) press and flat chest press, but many strength coaches suggest a 2:3 ratio. This means that if you cannot military press approximately 66% of your chest press weight, then you should focus on prioritizing the shoulder joint. A weaker shoulder may be forced into rotation during the bench press movement, and the resulting tension could seriously injure the rotator cuff. Following this benchmark (pardon the pun), a person who bench presses 200 pounds should be military pressing about 130 pounds.

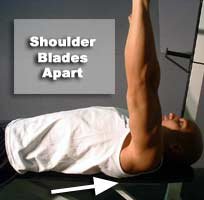

Another way to prevent shoulder joint injuries is to practice scapular retraction. Scapular retraction refers to squeezing your shoulder blades together. Many people do not have sufficient scapular control. When performing a bench press, you should perform scapular retraction and maintain this throughout the set. Scapular retraction forms a broader, more stable base against the surface of the bench, and also prevents the shoulder joint from rotating during the movement. A person who lacks sufficient scapular control will allow the retraction to cease, which places the shoulder joint in a vulnerable position that can lead to injury.

Scapular retraction is important for many exercises. Even a horizontal row involves scapular retraction. The proper execution of this movement involves retracting the scapula first, then pulling through with the arms. Lack of retraction at the start of this movement could, as in the bench press, result in an unnatural or unexpected rotation of the shoulder joint and lead to injury. Keeping the scapular retracted and the chest up and out also helps keep the back in proper alignment during movements that place tension on the spine, such as the squat and dead-lift.

Control Drills

Control Drill 1

To improve scapular retraction, you should perform a type of exercise known as a control drill. I recommend control drills before every upper body workout. Control drills do exactly what they imply - they improve control in a certain area. They also serve to warm up the target structure and prepare it for the workload it will receive. One very simple scapular retraction control drill involves lying face down on the bench.

Hang both arms down while grasping very light dumbbells (5 or 10 pounds maximum). Now, bend the arms at a right angle as if you are nearing the top of a row (an exercise that targets the back - this is like a one-armed row but with both arms). Keeping that angle, draw the shoulder blades together, squeeze them, hold, and relax. Your arms do not bend more nor extend during the movement; you are solely focusing on the scapula. The range of motion will only be a few inches or less.

You may also perform control drills for your rotator cuff. A few common control drills for the rotator cuff, all performed with extremely light weights (5 or 10 pound dumbbells at the most). The exercises can be performed lying or sitting. The pictures demonstrate some drills performed while sitting, with additional descriptions for the lying versions.

Anterior Rotation

Lie on your stomach on a table or a bed. Put your left arm out at shoulder level with your elbow bent to 90 degrees and your hand down. Keep your elbow bent and slowly raise your left hand. Stop when your hand is level with your shoulder. Lower the hand slowly. Repeat the exercise for 10 - 20 repetitions. Then do the whole exercise again with your right arm. Grasp a dumbbell if necessary.

Lateral Rotation

Lie on your right side with a rolled-up towel under your right armpit. Stretch your right arm above your head. Keep your left arm at your side with your elbow bent to 90 degrees and the forearm resting against your chest, palm down. Roll your left shoulder out, raising the left forearm until it's level with your shoulder. Lower the arm slowly. Repeat the exercise for 10 - 20 repetitions. Then do the whole exercise again with your right arm.

Lateral Rotation (Alternate)

Lie on your right side. Keep your left arm along the upper side of your body. Bend your right elbow to 90 degrees. Keep the right forearm resting on the table. Now roll your right shoulder in, raising your right forearm up to your chest. Lower the forearm slowly. Repeat the exercise for 10 - 20 repetitions. Then do the whole exercise again with your left arm.

Windmills

Simply straighten both arms then rotate forward 10 times, then reverse and rotate backwards. Start with small, slow circles and eventually increase the size of the circles and speed of rotation as your joint becomes accustomed to the drill.

Stretches

Stretches

A final, crucial element of shoulder joint stability is flexibility. You should perform light stretching before and moderate stretching after upper body workouts. Never stretch a cold muscle - warm-up your entire body by performing 5 - 15 minutes of cardiovascular exercise before stretching. Perform the following stretches for 10 - 20 seconds each, and then repeat for double that amount of time when the workout is complete.

Stretch 1

Hold your right arm straight across your chest, so your right hand is to the left of your body. Grab your right elbow with your left hand and pull your arm across your body. Repeat with the left arm.

Stretch 2

With your left hand, dangle a shirt or towel down over your back. Reach behind your back and grasp the other end with your right hand. While grasping the towel, pull up with your left arm so that your right hand travels up your back towards your neck. Repeat with the left arm.

Stretch 3

Sit on the floor and lean back on your arms. Focus on pushing forward with your torso while retracting your scapula and feel the stretch in your shoulders.

There are similar stretches and control drills for other critical joints such as the knee joint, hip joint, and elbow joint. To summarize the shoulder joint, here is a typical plan of attack for an upper body workout:

Upper Body Plan Of Attack

Upper Body Plan Of Attack

- 10 minutes of cardiovascular exercise (warm-up)

- Stretch 1: 10 seconds per arm

- Stretch 2: 10 seconds per arm

- Stretch 3: 20 seconds

- Scapular retraction drill

- Anterior rotation drill

- Lateral rotation drill

- Windmills

- Warm-up of 10 reps at 40% target weight

- Warm-up of 8 reps at 60% target weight

- Warm-up of 6 reps at 80% target weight

- Work sets (whatever the intended workout is)

- Stretch 1: 20 seconds per arm

- Stretch 2: 20 seconds per arm

- Stretch 3: 40 seconds

The stretches and drills may add significant time to the workout, but they will save time in the long run if it means you don't have to visit the doctor or stay at the hospital due to a rotator cuff injury!

The shoulder joint takes quite a bit of abuse, but it can be strengthened. By gaining control of your scapula and rotator cuff, you can lessen the potential for shoulder trauma. Any exercise that involves the shoulder joint will benefit from performing these stretches and drills, including the bench press. Consider adding these injury-prevention techniques to your own plan as you progress to your peak physique!